Sweet Blood at Center Stage: Camille Simone Thomas and Raecine Singletary on Legacy, Joy, and Resistance

In Sweet Blood, memory hums like a drumbeat. Three Afro-Taíno Maroon sisters navigate love, legacy, and liberation in colonial Jamaica, each step echoing those who came before them. Written by Camille Simone Thomas and directed by Raecine Singletary, this new play doesn’t just tell a story—it resurrects one.

In this Center Stage conversation, we step into the rehearsal room to witness how these two artists build worlds from history’s silences: blending research, ritual, and imagination into a work that feels both ancestral and alive. Produced in collaboration with Black Girls Do Theater, Sweet Blood is a testament to the power of Black women reclaiming narrative, one line, one sister, one song at a time.

Talk to us about Sweet Blood. Was there a place or story from your own background that helped you ground the play’s sense of place?

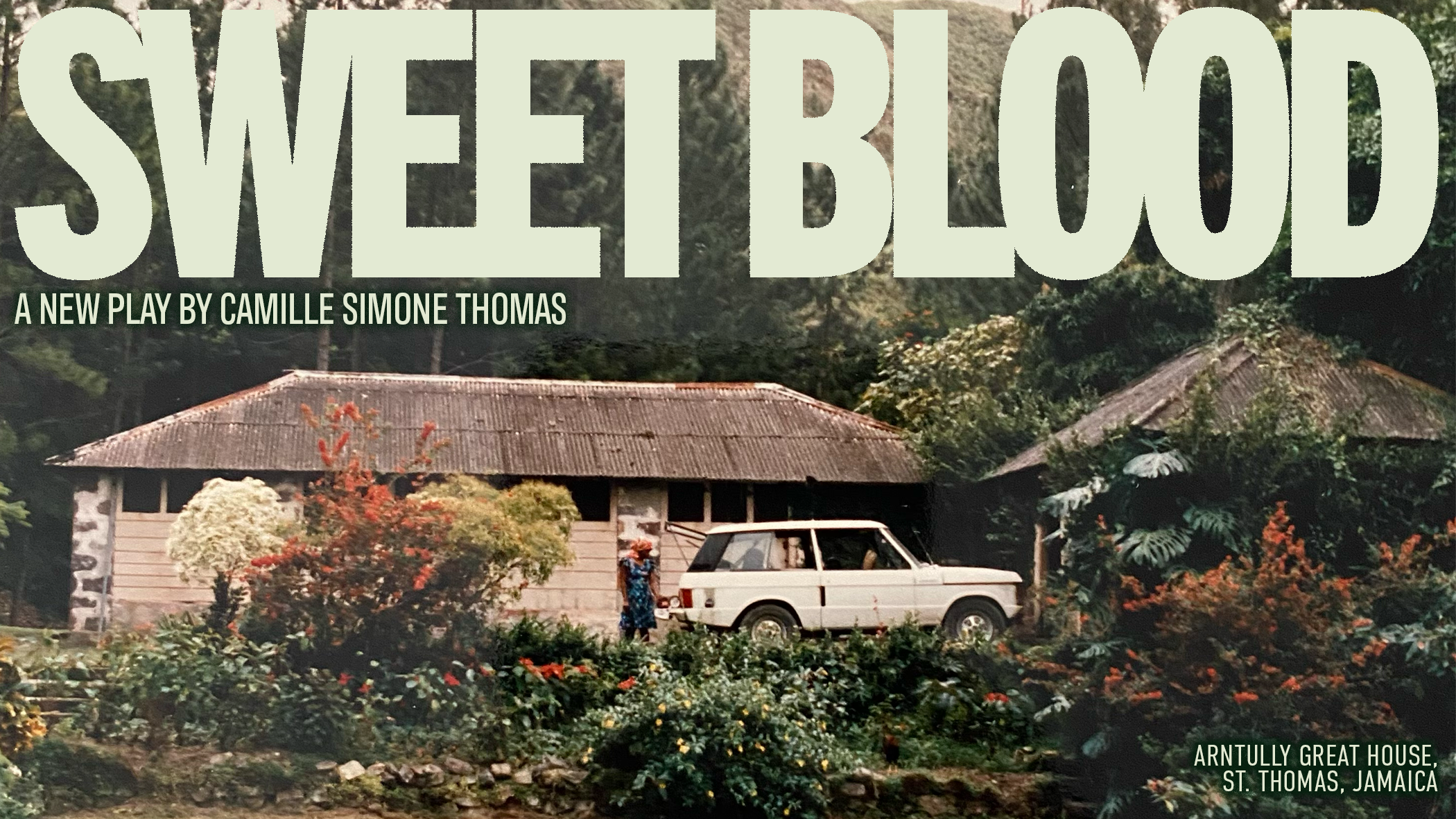

Camille Simone Thomas: My grandparents used to have this home in Jamaica, and I had never been there, but I grew up always seeing pictures of this home, and so I was intensely curious about it, and one of my biggest dreams is to buy this home back and turn it into an artist residency for Jamaican artists who are living abroad to come back and create work on the island.

So I started doing my own research, and I was like, how much would it cost to buy it? Just how much? I'm curious. And then I found out that this place used to be a coffee plantation, so that made me really interested. And then another thing that was happening, I'm pre-diabetic, so I was thinking a lot about sugar, and how we interact with sugar, and how sugar interacts with our bodies, and I talked to a mentor, and she was like, you know, that's epigenetics.

We all have diabetes or pre-diabetes, because our people were eating sugar cane in the mountains. All of these things were coming together to form a story, and as a playwright, I typically write about women and women's stories, and I was also interested in resistance. I think we're in a period in time where we need to be resisting more, and I knew my ancestors have resisted in the past, so I would just started writing the story from there.

Raecine, the first time that you read Sweet Blood, can you talk to us about that moment?

Raecine Singletary: I have a biased opinion on all of the work, so it was very much like, I'll read anything you set my way. But I loved it, because first, Camille is still like one of the few playwrights and authors where I like, was the first time I got to witness Jamaican culture and like patois on the stage.

I was like, oh my gosh, I can combine where I like my culture and my love for theater together, so Camille was definitely the eye-opener for that. So reading Sweet Blood, I was like, oh, this is just another level of it. It was just another layer of what we could do in bringing light to the past Jamaican experience, but also bring it into the theater.

So it was really exciting. My first thought was definitely, I can't wait for my mom to read this. I can't wait to tell my grandmother about this.

It's opened up conversations for myself and my grandmother, who is from maroon heritage, to talk about her experience. So it's a really exciting time, as all Camille Simone Thomas plays are.

Renee Harrison: Echoing that, I've read quite a few plays about Jamaica and its people. There's Elmina's Kitchen, there's Playboy of the West Indies, but what makes Sweet Blood really stand out is where it lives in history. Most of the plays I’ve mentioned have been about 20th century Jamaica.

You two have built such a beautiful creative shorthand over the years. What’s different about your collaboration on Sweet Blood — and what feels the same?

CST: We've worked together four or five years now. So I think just honestly, Raecine is my sister.

Seeing her grow as a director and seeing her grow with her ideas, I think that's different. Like I've always trusted her when I met her. We’ve worked on an enhanced reading. We worked on a couple of different things. She's talented. She is Jamaican. I trust her.

RS: I love telling the story of how Camille and I met. It was on Zoom. We’d both signed up for the Lime Arts 20 by 20 Fringe Festival.

We didn't actually meet in person until what, like a year, two years later when I came to the city. But it's been this the whole time after that, like after the first date jitters, it was like, this is definitely sister for life. And so this is very much the dynamic is very much the same, but echoing what you said of the difference.

CST: It's just like, we've both grown separately in the best way possible. And then so when we come together, we can continue to strengthen each other as we're like strengthening our work. I hope that Sweet Blood is a reflection of that.

How do you and Camille balance trust and challenge in your process — that dance between protecting the vision and pushing it further?

RS: Logistically, I like to have a couple of meetings with Camille before we start. My question for her is always “What do you hope to get out of this?” So I'm not coming into the room as a playwright, I'm not helping her to expand this piece, especially when it's a piece that is continuously in development.

She can trust that I have her goals and her desires in mind.

CST: I trust the people that she brings — the designers, the actors. She's so great at building a team. I feel like I'm good at strengthening that.

I’ll add transparent conversations as well. I don't think I've ever hated or really even disliked anything Raecine did.

You describe the play as being a work of historical speculative fiction How did you navigate that tension between what you knew and what you had to dream in order to make the world of Sweet Blood whole? Particularly, when the archive refuses to tell the whole story.

Photos provided by Camille Simone Thomas

CST: Octavia Butler has this quote, “There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns”

So thinking about the in which I live my life as a black woman as a black girl, my first question was: What are the things that I do with my sisters?

We do each other's hair. We used to wrestle all the time. We were very rough. So, I imagine that these sisters in 1727, we're still doing each other's hair, maybe still wrestling.

I was able to talk with one of my PhD friends, and she introduced me to Saidiya Hartman's Critical Fabulation, which is building upon or filling in the gaps of the archive. Too, I read the essays of a Jamaican scholar, Dr. Marcia Douglas, and she talks about investigating the archive of dream, imagination and memory.

Because I questioned: is this valid? I never want to disrespect, I never want to offend. My culture means so much to me, but I am African American and Jamaican, and I was raised here in America. So I understand there is a distance that I have.

Being able to read Jamaican scholars who have done more work than me, who are older than me, being able to have conversations with other Jamaican creators and artists. Raecine is Jamaican, you are Jamaican, Jordan, our other co-producer is Jamaican. With this iteration, I was very intentional in casting our three sisters are all Jamaican.

Having conversations in the room of “What is this shared history that we might all have?”, really helps me to continue dreaming and imagining in community.

From the moment that Sweet Blood comes to you, what is your starting point for the story? Where do you begin in your process as a writer?

CST: I started with the sisters relationships. They were all very distinct in who they were as characters, and then I put these characters in conversation with each other.

I was thinking so much about sugar and sugar cane. What is my relation to sugar and sugar cane? I remember being young and eating it and having some of the juice drip down my face and it being sticky, and so a lot of the tactile sensations grounded me.

When I think of Jamaica, I think of mosquitoes. Oh my god, I know mosquitoes were alive in 1727. I know that is a fact. So I'm like, okay, I'm sure the girls would still be trying to hit the mosquitoes away, and then I build this world sensorially from there.

In your development of this play, when did you know that men had to be a part of it? Why did you choose to posit them in the way that you did?

CST: Because this play is exploring colonialism and oppression, I was interested in the ways that Black men oppress Black women, but also understanding that they are being oppressed by a larger colonial force: white supremacy. They are being pressed down and then they are pressing down upon us. So I knew they had to be in there to explore that relationship.

I will say, Kosey and Cyrus, who are the two Black male characters, they grew so much when we were at North American Cultural Laboratory. I had Aaron J. Anderson playing Cyrus, and then Booker Vance played Kosey. They had so many questions and so many curiosities about the world.

Having those wonderful conversations with them, I knew I wanted to explore as much as possible with these two male characters, understanding that this is still a story about the sisters.

I also wanted the audience to walk away having chosen different sides: 25% of siding with Kosey, another 25% with Cyrus, and then 50% of the audience to side with the sisters.

Raecine, returning to an earlier question, is there a place, story, or ritual from your own background that helps you to ground the play's sense of place in your directorial process?

RS: I have rituals that ground sense of place in the rehearsal room, like regardless of where we are and how I like to start and end all of my rehearsals.

I've been thinking a lot of my grandmother and she spent time in the mountains. My great grandfather is Maroon and she spent a lot of time with him. And so thinking about the way that she would walk up the mountain the same way that the girls are.

And what is that, talking about sensory, like what is that physical work and exhaustion, but also excitement to see someone that you love and reflect in the girls and their relationship. And then also in the very base, I think of what grounds me overall as an artist is this term of revolutionary joy. This joy is a tool and means of survival, especially for black Americans, for black girls, for Jamaican women and on.

We are all invested in creating space for Black women artists. How did Sweet Blood become a reflection of that mission — not just onstage, but in the room itself?

RH: For me, very similarly to Camille, when I think about home, Jamaica means so much to me. At the opportunity to help support this story that is written by a Jamaican woman, directed by a Jamaican woman, and it is about these three young Jamaican women who are navigating a really difficult time in history, I knew I had to say YES.

CST: The way I make space for Black women and Black girls in theatre is believing, knowing and seeing that we are competent. Oftentimes, we have to prove something, we have to show that we deserve to be here.

Then still leaving space for curiosity and for that growth. Leaving space for those mistakes to happen and not being so rigid.

One of our actors today, actually, one of our Black male actors, I asked him a question about his character. And he was trying to think, eventually saying “I think this is a trick question.”

I reassured him that I wasn’t trying to trick him and inquired a bit further: Why do you think that? He said: I went to a PWI and I'm used to having to find the answer and then it not being the right answer, then feeling like I got tricked and then feeling like I got trapped and just, feeling like all of these things.

And fortunately, no, this is not your predominantly white institution. I am genuinely interested in your thoughts on this character and how you are approaching this.

RS: I just try not to give up.

I want to be here and I need to be here because if I can say that I did it, then maybe somebody, another Black girl, can see me and do it too.

I went to a PWI as well and while I'm grateful for my education, I didn’t have a network of other Black women who’d already made it as directors. I had to go outside of my institution to find that and to find folks who could help me. I’m not giving up because someone may find me one day, in search of a peer, and I want to be able to support them. So that's my drive in continuing day-to-day and practicing my craft.

If your ancestors could sit front row at a performance of Sweet Blood, what do you hope they’d whisper to you after the curtain falls?

CST: I just hope they're proud of me. I hope they say good job.

I picture my grandmother who passed away like a year ago. She was a very Brooklyn grandma. She was nowhere near Jamaican, and at a very inappropriate time she would scream out, That’s My Baby. That’s what I’d hope for.

RS: If my great grandfather was in the audience, or my great grandmother, the first thing that comes to me is them leaning in and asking, How'd you know? How'd you know that's what it was? I’m getting emotional thinking about it because we are more connected than we think. You may not have the documented history of it, but I have the history of it. It's so ingrained in me and because of that, we do get some of the things right. We do know, I do know.

RH: I imagine that they'd say thank you. Not just for the story, but for the fact that they likely couldn't imagine a world in which you two would be doing this, that we'd all be doing this.

Sweet Blood plays at JACK, 20 Putnam Ave, Brooklyn, NY

November 6th-8th. Grab your tickets here.